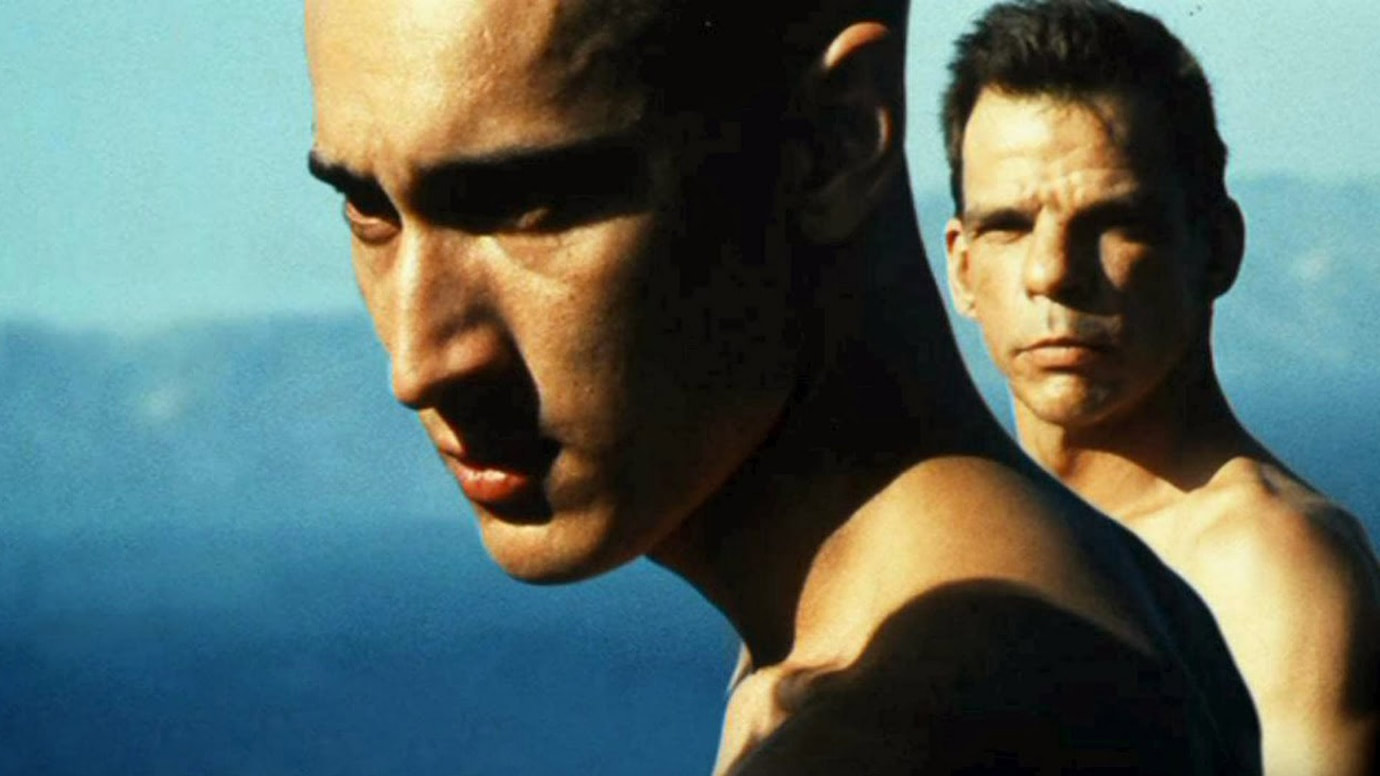

The film follows Legionnaires based in Djibouti, West Africa. The story is somewhat loose but it centres around three main characters – Chief Master Sergeant Galoup (Denis Lavant), his superior Bruno Forestier (Michel Subor), and a new recruit Gilles Sentain (Gregorie Colin). When Sentain joins the legionnaires as a new recruit Galoup is jealous although it’s never made clear exactly why. It’s suggested that it’s his youth, beauty and the fact that he is not running from a violent or difficult past that have Galoup riled. Galoup devises a plan to provoke Sentain into reacting then punish him for it – potentially getting rid of him forever. Galoup’s intentions are discovered and he’s ejected from the Legion to struggle with a civilian life he says he is unfit for. On paper Beau Travail is a very traditionally masculine film about a militant force, jealousy and murderous intentions. But the reality far from it, this film feels more like a ballet. Other films about military forces may open with violence or shows of force in order to assert the power, anger and danger that surrounds these men. But here we first see the legionnaires standing perfectly still and silent, arms raised straight into the air like tree trunks, all facing different directions. It is as though these human bodies are at one with their surroundings, both powerful and natural. The Legionnaires are frequently shown performing their training routines in a drawn out choreography. They demonstrate great strength, agility and flexibility but it is controlled and they are mostly silent. Even when Galoup and Santain face off against each other it is more akin to a tango. Both parties strut around each other in a circle and the camera creeps closer and closer to their faces. But they don’t come to blows. This is about posturing and performing a dance, not physical fighting. Some would accuse Denis (and her female Director of Photography Agnes Godard) of a reversal of the male gaze into something of a female gaze. But the male gaze is not just about the act of looking at women’s bodies, it is a reduction of them.

The camera clearly appreciates the men’s bodies and the audience is invited to marvel at their power, muscles and agility. But the way they are photographed does not reduce and objectify them in the same way as the male gaze does to women’s bodies. The men are also shown as having complex emotions and pasts. There is a quiet contemplative atmosphere to much of the film and there is no physical violence and the drama is more psychological than adrenaline fuelled action. In places the music is a crescendo of chanting male voices. Like the bodies on screen it evokes unity and passion but is also beautiful and graceful. This is a masculinity that is both deeply emotional and physically strong. A counter to the toxic masculinity narrative which sees sensitivity or beauty as weak and un-masculine. The overall tone is remorseful and bound in memories. In a voiceover Galoup says that “freedom begins with remorse” and those words ring true in the final scenes. Galoup lays on his bed considering his terrible actions and clutching a gun. As the camera pans to his arm a vein visibly pulses under his skin and his tattoo reads “Serve the good cause and die”. His veins are full of life but he feels he has come to the end and it’s time to die. He is remorseful and seeks freedom. The final scene though is not one of suicide but of dancing. Galoup is in the club dancing with frenzied abandon to Corona’s “Rhythm Of The Night”. His leaping and rolling mirror the movements we saw earlier but this time it’s a raw expression, not a discipline. As this scene is set apart from the narrative of the film some see this as a reflection of his soul after his death. Some see it as him choosing to live with freedom after a life of structure. However you choose to read the scene it is rather powerful. After dancing in the desert in something akin to a ballet he now lets loose and expresses what’s really inside. After twenty years this film offers a masculinity which is much needed today. It’s a poetic celebration of emotion, self reflection and remorse. And an appreciation of men’s bodies as silently supple, powerful yet graceful.

As praise rolls in for "Fight Club" and it's 20 year anniversary, it's very much worth another look at “Beau Travail”. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorHi, I'm Caz. I live in Edinburgh and I watch a lot of films. My reviews focus mainly on women in film - female directors or how women are represented on screen. Archives

December 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed