|

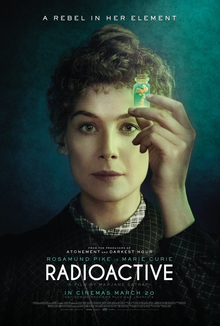

We meet Marie as Maria Skłodowska (Rosamund Pike), a Polish immigrant living in Paris and “taking up too much space” in a shared laboratory. She is informed by a roomful of men that she is being kicked out and she must find another if she wants to continue her scientific endeavours. She’s sharp and hardened, far too used to not taking crap from anyone and having to stand her ground to be really close to anyone. She meets Pierre Curie (Sam Riley) and through some quick montages they marry and set up a new lab together. As a partnership they discover two new elements, stunning the scientific world and produce two children. When Pierre dies Marie struggles to recover. News that radioactivity is actually making people sick starts to spread and she becomes a pariah. She’s also increasingly sick herself so her final life’s goal becomes to use her discoveries on the front line and save the lives and limbs of soldiers along with her daughter Irène (Anya Taylor-Joy). This felt like a good, albeit rambling, introduction to Marie Curie’s life. We learn about her personality, her work, her personal life, and her struggle to be accepted as a woman in the scientific community. There wasn’t really one central aim of the plot though, except to tell us about Marie Curie. This approach works really well in some films as we’re absorbed into the main character’s life. But here it felt disjointed. The structure and style are distinctive with some very bold visual choices being made. There were extended scenes from the future showing various positive and negative effects of her discoveries. We see a hospital in the 1950s administering radiotherapy for cancer treatment, atomic bomb testing in Nevada (tread carefully, fellow uncanny valley sufferers, there are some horrific mannequin ‘deaths’), and Hiroshima ‘what’s that in the sky’ enactments. These extended jumps in time have nothing to do with the main plot. After all, Marie Curie had no idea at the time that these specific events would happen. But the spectre of a potentially disastrous future weighs on Curie’s mind so it kind of makes sense for the tone of the film but not the narrative. The fusion design of the film mixes 1930s Paris with bright animated ‘science stuff’ and electronic soundscapes. It makes for a modern and bold look that doesn’t always work. The 1930s design has golden shafts of dusty sunlight bathing window panes, and arrays of gorgeous glass bottles and jars. Not quite mad scientist Frankenstein aesthetics but a more sumptuous version. The flash-forward extended scenes were very stylised too, each with a clear colour scheme and clean-cut design. The fantastical animated imaginings of glowing uranium and planetary forces likely worked very well in the graphic novel “Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie: A Tale of Love and Fallout” by Lauren Redniss which served as a source. But it felt a bit out of place on the big screen, unfortunately. On the audio, the sound on the outdoor dialogue seemed off, as though they were speaking in a well-muffled room far away from the outdoor space we see them in. It was offputting enough to make me wonder whether the microphone had failed and they had to re-record entire scenes in a sound booth later on. Or perhaps it was just the tone of the speakers in my cinema making those scenes oddly muffled. Despite a structure and choppy visuals that have the potential to turn people off, it is still absolutely fantastic to see a film about such an incredible, strong and inspiring woman from history. And one who had such a lasting impact on all of our lives. We get to learn about her as a real person, with ambitions and conflicts. The clash of design and effects was a visionary move which I completely respect and admire even though it didn’t work for me personally. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorHi, I'm Caz. I live in Edinburgh and I watch a lot of films. My reviews focus mainly on women in film - female directors or how women are represented on screen. Archives

December 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed