|

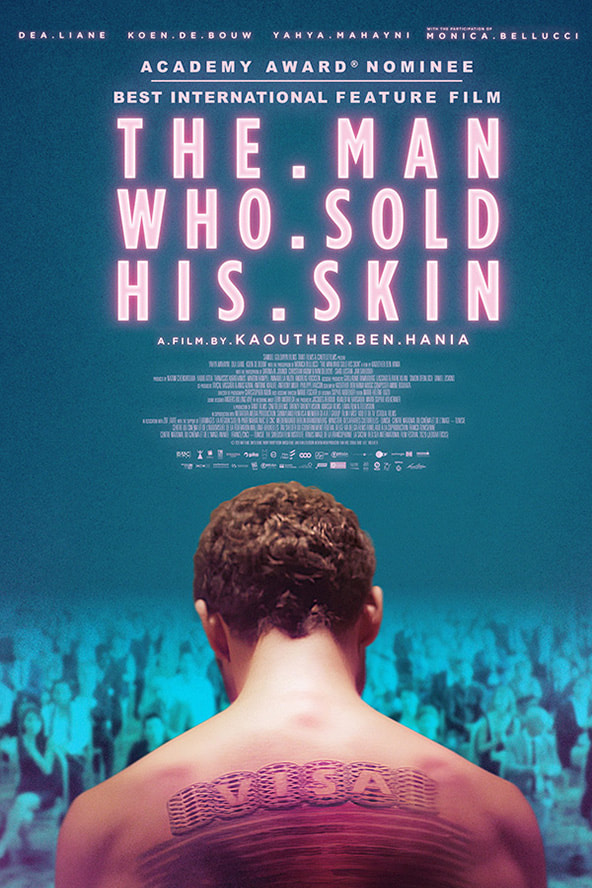

Sam (Yahya Mahayni) is a Syrian refugee living in Lebanon struggling to get by and separated from his lover. By chance he meets a rich provocative artist Jeffrey Godefroi (Koen De Bouw) who “turns worthless objects into works that cost millions and millions of dollars just by signing them”. Godefroi offers Sam the chance of a new life and a Schengen visa by physically becoming his next piece of art. Sam has his entire back tattooed by the artist and gains what feels like freedom and luxury. But his movement is still restricted and he is literally owned by someone else. He becomes both a poster-child for the exploitation of refugees and a celebrated artwork. “I just made Sam a commodity. A canvas.” The tone of this film is relatively light compared to the subject matter as Sam injects natural humour into serious situations. It’s not presented in a dark and disturbing atmosphere but the issue at hand is incredibly important nonetheless. Here we have a human being who is literally turned into an object and is bought and sold as such. It’s clearly an exploitative thing to do to another human being but there is a seed of doubt planted in our minds which helps us to consider the issue from a different angle. The question raised is whether Godefroi’s actions raise the profile of the plight of refugees and in doing so might help others. He claims to be making a point about commodities having more freedom of movement than people… by turning a person into a commodity. Of course Godefroi did not have any noble intention, he just wanted to exploit Sam and other refugees for personal gain. But it raises that more universal question in viewers’ minds as to whether a bad act is justified if it has positive consequences. At the other end of the scale is a refugee rights group who protests against Sam’s treatment, bringing a voice to what the audience is already thinking. You can’t abuse another human being’s dire situation and display him as an object. But even this attitude is met with a counter argument that Sam is living in luxury. He doesn’t personally feel exploited. This raises the question of how personal feelings and opinions fit with what’s good for the whole. Is Sam furthering the exploitation of others, or is it simply his personal choice to be happy? This layering of perspectives gives the film a lot of depth. Even though viewers would (hopefully) understand that what Godefroi and others did to Sam was completely abhorrent, by looking at the topic through different angles we can explore it better, and hopefully come out stronger in our beliefs. Certain imagery used throughout the film supports the themes without being overbearing. Animals are shown as being a commodity, and Sam himself is called an animal at one point. This brings to mind the rights of all living creatures as well as the relative rights of some humans in comparison to animals. One shot includes decorated statues of pigs in an art gallery. This is a reference to the original artist on which the film drew inspiration. Wim Delvoye tattooed the back of Tim Steiner who, like Sam in the film, must sit in various art galleries as a live exhibit when required. Delvoye also tattooed (thankfully sedated) pigs to turn them into artworks whose skins are then sold when they die of old age. Mirrors, echoes and reflections are also used throughout. This raises the idea of voyeurism and examination. The act of looking itself and the effect that has on the subject. Also, the idea that this exploitation might be echoed many times over with other people in different ways. In that sense Sam’s position is not unique. Indeed, Sam’s lover Abeer (Dea Liane) faces her own exploitative dilemma. She must decide whether to escape the violence in Syria by marrying a man she doesn’t love. Millions of women around the world face the prospect of having shelter and financial security at the expense of their freedom and being exploited by the men in their lives. Yet this is dismissed by Sam as being nothing like his situation. The ending is the only slight letdown as it softens the intensity of the rest of the film a bit too much and lets the viewer off the hook too easily. But the film as a whole is incredibly chilling, forcing us to consider bodily autonomy, exploitation vs personal responsibility, the nature of art, and how much people really care about the plight of others. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorHi, I'm Caz. I live in Edinburgh and I watch a lot of films. My reviews focus mainly on women in film - female directors or how women are represented on screen. Archives

December 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed